September 19, 2025

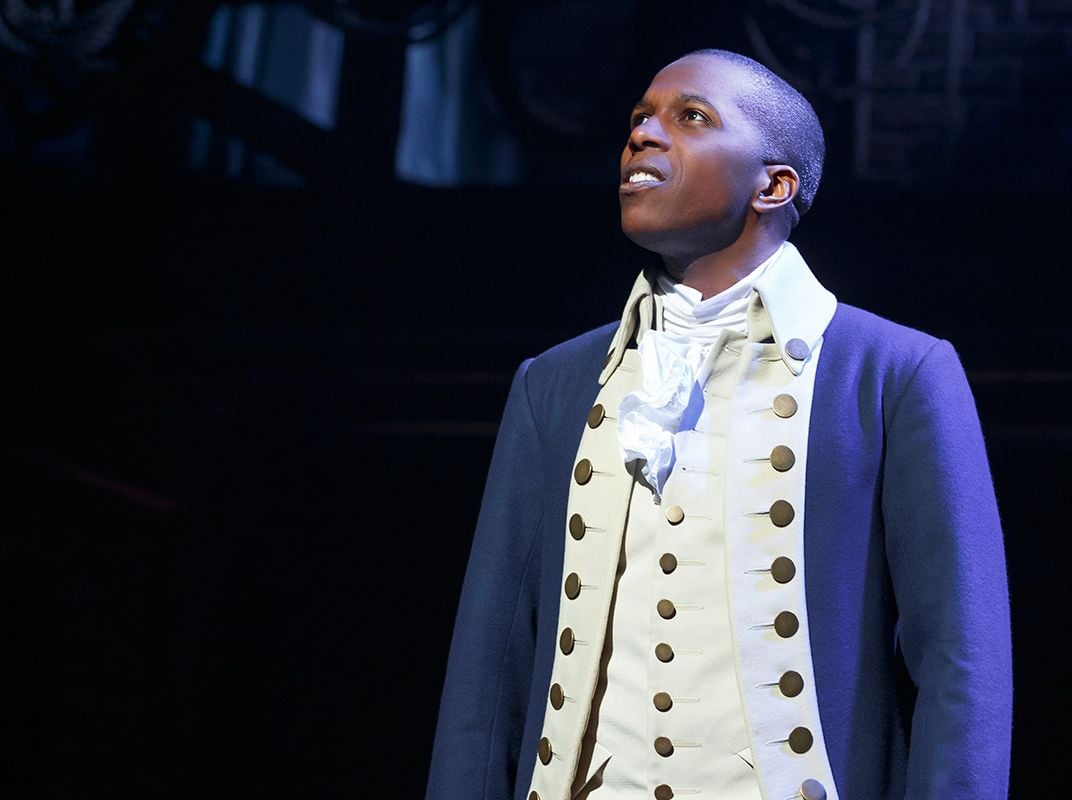

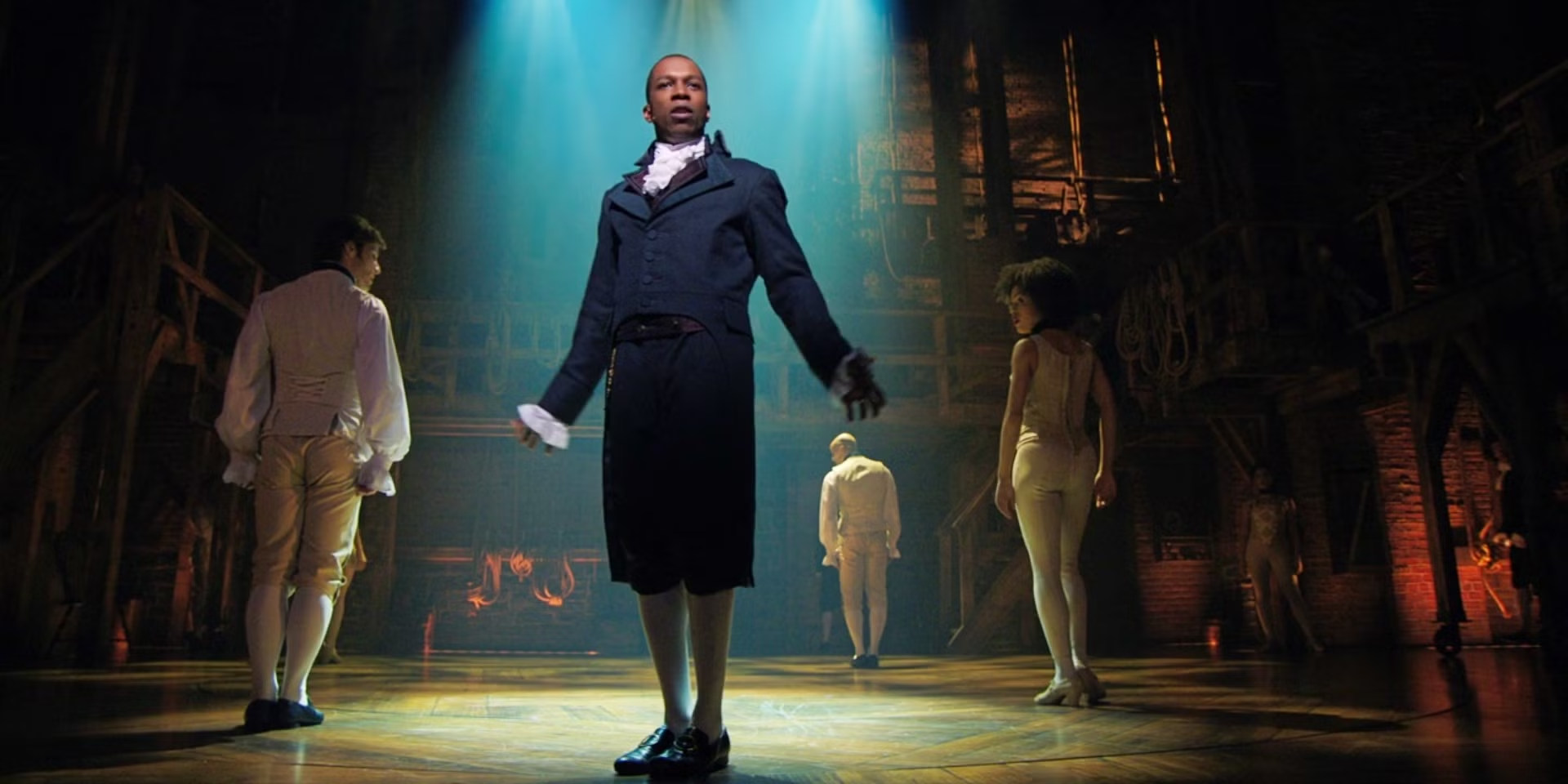

As someone who’s battled impostor syndrome for most of her life, I’ve often struggled with the feeling of not belonging — especially in a classroom or a job. In my first full-time job (before UX), I felt so out of place; every person walking into my manager’s office was someone who could be telling them I shouldn’t be there. I’ve felt it in my current career, too — that nagging voice in the back of my head, which gets louder when things feel uncertain. Like Aaron Burr, I longed to be in “The Room Where It Happens,” but I never thought I deserved an invitation. In the last few months, however, something shifted — something I didn’t recognize until presenting design team updates to a room full of executives: I had been in “The Room Where It Happens” for quite some time; I just didn’t fully realize it.

For lack of a better term, the paranoia that goes hand-in-hand with impostor syndrome is exhausting. Every errant word, every action felt scrutinized. Coming out of bootcamp, I felt so green, so unable to answer questions I knew I had the answer to. It tripped me up in meetings, bogged me down when it came to writing surveys or interview scripts, and left me constantly second-guessing interactions with my coworkers. I found myself double-checking everything with my mentor and later, my fellow designers.

The slow shift to confidence is subtle, and mine happened during a high-stress time in my life. Ever-changing roadmap priorities and a significant leadership change left me feeling as though I were on shifting sands, with no way out. Workplace bullies didn’t help this, either — barely polite comments in Figma files telling me to “educate myself” killed my confidence and upped my paranoia, especially when friendly coworkers told me what was being said behind my back.

But my work spoke for itself, and despite this, I started standing tall, planning my own projects and executing them, and building genuine relationships with my coworkers. I began to advocate for my work — often out of annoyance or frustration — and while I still questioned if I was doing things the right way, I no longer questioned my basic knowledge. In some ways, I couldn’t afford to ask this anymore. I didn’t have a design lead to help or protect me, so I had to find ways to grow, to speak up, to move forward.

As a theater kid, I knew how to put on a confident air, but it wasn’t until I started interviewing designers for a job at EverDriven that I actually began to feel it. The designer we hired commented on it shortly after she started, telling me she’d “assumed I was a senior designer” based on my knowledge and how I spoke. It opened my eyes to the change: I could talk the talk, and, upon reflection, I had been walking the walk for a while. I stopped going to my coworkers to ask if I was doing things right, and instead went to them to ask for opinions. I was still advocating angrily, but I was doing better at asking the questions that needed to be asked. If a feature or UI change were suggested, I’d ask about user validation: where was the request coming from? Did we know this would provide value to the users, or were we doing this so we could quickly “add value?”

The pushback helped me strengthen my voice, and as EverDriven leadership began to stabilize, I found peers I could not only lean on for support but also trust to discuss growth. I felt the same nurturing I had under my old design lead, but now I had the voice to ask for what I wanted: growth. Now I could make plans, and I had the hard-won courage to talk about what I was doing and what I needed to keep going.

Even though I’ve realized I can talk the talk, that I wasn’t “Talking Less and Smiling More,” the impostor syndrome still lingers. I still experience anxiety over certain decisions, and my hands still tend to tremor during public speaking (similar to the “bonus vibrato” I used to get in auditions). Despite this, I’ve found I’m not questioning my intelligence, my knowledge, or my right to be in “The Room Where It Happens.”

If you find yourself in that hazy space between wondering if you belong and knowing you do, the best course of action is action. You won’t wake up one day with newfound confidence; you have to work at it. You have to prove to yourself that you belong, that you know what you’re talking about. After all, we are our own worst critics! Advocacy, even out of frustration, is still advocacy. It’s the best way to practice standing up for yourself. Even “faking it ‘til you make it” is a viable strategy — so long as you’re faking your confidence, not your knowledge.

It took a long time to realize I’d gone from singing “I want to be in the room where it happens” to understanding I was already there. While my journey didn’t involve elections and duels, it did include finding ways to create confidence in myself, despite the stresses and the self-doubt I faced. It was a long trip to get here, and I suspect it isn’t entirely over. And to all of my fellow impostors: the next time you’re questioning if you fit in, if you’re smart enough, if you’re knowledgeable enough, look around. Odds are, you’re already in the room, because someone thought you belonged there.